P2P Data Sync for Mobile

Together with decanus, I’ve been working on the problem of data sync lately.

In building p2p messaging systems, one problem you quickly come across is the problem of reliably transmitting data. If there’s no central server with high availability guarantees, you can’t meaningfully guarantee that data has been transmitted. One way of solving this problem is through a synchronization protocol.

There are many synchronization protocols out there and I won’t go into detail of how they differ with our approach here. Some common examples are Git and Bittorrent, but there are also projects like IPFS, Swarm, Dispersy, Matrix, Briar, SSB, etc.

Problem motivation

Why do we want to do p2p sync for mobilephones in the first place? There are three components to that question. One is on the value of decentralization and peer-to-peer, the second is on why we’d want to reliably sync data at all, and finally why mobilephones and other resource restricted devices.

Why p2p?

For decentralization and p2p, there are both technical and social/philosophical reasons. Technically, having a user-run network means it can scale with the number of users. Data locality is also improved if you query data that’s close to you, similar to distributed CDNs. The throughput is also improved if there are more places to get data from.

Socially and philosophically, there are several ways to think about it. Open and decentralized networks also relate to the idea of open standards, i.e. compare the longevity of AOL with IRC or Bittorrent. One is run by a company and is shut down as soon as it stops being profitable, the others live on. Additionally increasingly control of data and infrastructure is becoming a liability. By having a network with no one in control, everyone is. It’s ultimately a form of democratization, more similar to organic social structures pre Big Internet companies. This leads to properties such as censorship resistance and coercion resistance, where we limit the impact a 3rd party might have a voluntary interaction between individuals or a group of people. Examples of this are plentiful in the world of Facebook, Youtube, Twitter and WeChat.

Why reliably sync data?

At risk of stating the obvious, reliably syncing data is a requirement for many problem domains. You don’t get this by default in a p2p world, as it is unreliable with nodes permissionslessly join and leave the network. In some cases you can get away with only ephemeral data, but usually you want some kind of guarantees. This is a must for reliable group chat experience, for example, where messages are expected to arrive in a timely fashion and in some reasonable order. The same is true for messages there represent financial transactions, and so on.

Why mobilephones?

Most devices people use daily are mobile phones. It’s important to provide the same or at least similar guarantees to more traditional p2p nodes that might run on a desktop computer or computer. The alternative is to rely on gateways, which shares many of the drawbacks of centralized control and prone to censorship, control and surveillence.

More generally, resource restricted devices can differ in their capabilities. One example is smartphones, but others are: desktop, routers, Raspberry PIs, POS systems, and so on. The number and diversity of devices are exploding, and it’s useful to be able to leverage this for various types of infrastructure. The alternative is to centralize on big cloud providers, which also lends itself to lack of democratization and censorship, etc.

Minimal Requirements

For requirements or design goals for a solution, here’s what we came up with.

-

MUST sync data reliably between devices. By reliably we mean having the ability to deal with messages being out of order, dropped, duplicated, or delayed.

-

MUST NOT rely on any centralized services for reliability. By centralized services we mean any single point of failure that isn’t one of the endpoint devices.

-

MUST allow for mobile-friendly usage. By mobile-friendly we mean devices that are resource restricted, mostly-offline and often changing network.

-

MAY use helper services in order to be more mobile-friendly. Examples of helper services are decentralized file storage solutions such as IPFS and Swarm. These help with availability and latency of data for mostly-offline devices.

-

MUST have the ability to provide casual consistency. By casual consistency we mean the commonly accepted definition in distributed systems literature. This means messages that are casually related can achieve a partial ordering.

-

MUST support ephemeral messages that don’t need replication. That is, allow for messages that don’t need to be reliabily transmitted but still needs to be transmitted between devices.

-

MUST allow for privacy-preserving messages and extreme data loss. By privacy-preserving we mean things such as exploding messages (self-destructing messages). By extreme data loss we mean the ability for two trusted devices to recover from a, deliberate or accidental, removal of data.

-

MUST be agnostic to whatever transport it is running on. It should not rely on specific semantics of the transport it is running on, nor be tightly coupled with it. This means a transport can be swapped out without loss of reliability between devices.

MVDS - a minimium viable version

The first minimum viable version is in an alpha stage, and it has a specification, implementation and we have deployed it in a console client for end to end functionality. It’s heavily inspired by Bramble Sync Protocol.

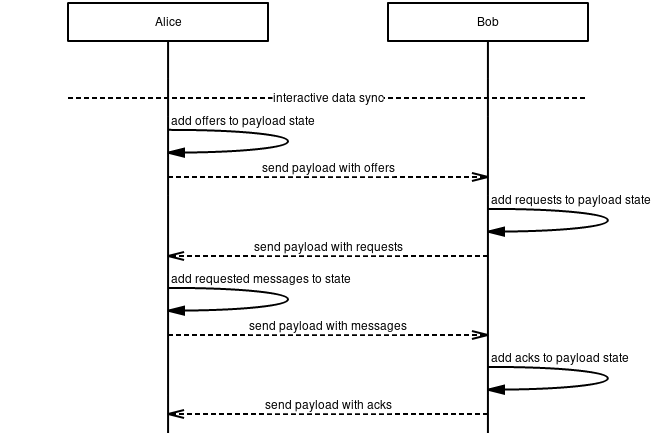

The spec is fairly minimal. You have nodes that exchange records over some secure transport. These records are of different types, such as OFFER, MESSAGE, REQUEST, and ACK. A peer keep tracks of the state of message for each node it is interacting with. There’s also logic for message retransmission with exponential delay. The positive ACK and retransmission model is quite similar to how TCP is designed.

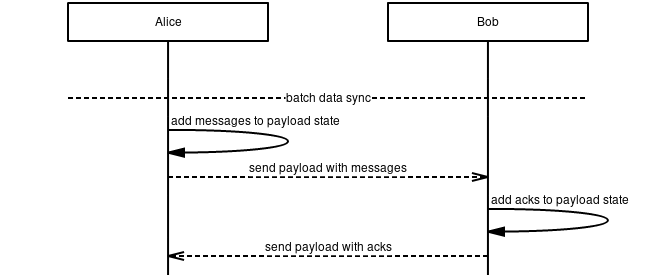

There are two different modes of syncing, interactive and batch mode. See sequence diagrams below.

Interactive mode:

Batch mode:

Which mode should you choose? It’s a tradeoff of latency and bandwidth. If you want to minimize latency, batch mode is better. If you care about preserving bandwidth interactive mode is better. The choice is up to each node.

Basic simulation

Initial ad hoc bandwidth and latency testing shows some issues with a naive approach. Running with the default simulation settings:

- communicating nodes: 2

- nodes using interactive mode: 2

- interval between messages: 5s

- time node is offine: 90%

- nodes each node is sharing with: 2

we notice a huge overhead. More specifically, we see a ~5 minute latency overhead and a bandwidth multiplier of x100-1000, i.e. 2-3 orders of magnitude just for receiving a message with interactive mode, without acks.

Now, that seems terrible. A moment of reflection will reveal why that is. If each node is offline uniformly 90% of the time, that means that each record will be lost 90% of the time. Since interactive mode requires offer, request, payload (and then ack), that’s three links just for Bob to receive the actual message.

Each failed attempt implies another retransmission. That means we have (1/0.1)^3 = 1000 expected overhead to receive a message in interactive mode. The latency follows naturally from that, with the retransmission logic.

Mostly-offline devices

The problem above hints at the requirements 3 and 4 above. While we did get reliable syncing (requirement 1), it came at a big cost.

There are a few ways of getting around this issue. One is having a store and forward model, where some intermediary node picks up (encrypted) messages and forwards them to the recipient. This is what we have in production right now at Status.

Another, arguably more pure and robust, way is having a remote log, where the actual data is spread over some decentralized storage layer, and you have a mutable reference to find the latest messages, similar to DNS.

What they both have in common is that they act as a sort of highly-available cache to smooth over the non-overlapping connection windows between two endpoints. Neither of them are required to get reliable data transmission.

Basic calculations for bandwidth multiplier

While we do want better simulations, and this is a work in progress, we can also look at the above scenarios using some basic calculations. This allows us to build a better intuition and reason about the problem without having to write code. Let’s start with some assumptions:

- two nodes exchanging a single message in batch mode

- 10% uniformly random uptime for each node

- in HA cache case, 100% uptime of a piece of infrastructure C

- retransmission every epoch (with constant or exponential backoff)

- only looking at average (p50) case

First case, no helper services

A sends a message to B, and B acks it.

A message -> B (10% chance of arrival)

A <- ack B (10% chance of arrival)

With a constant backoff, A will send messages at epoch 1, 2, 3, .... With exponential backoff and a multiplier of 2, this would be 1, 2, 4, 8, .... Let’s assume constant backoff for now, as this is what will influence the success rate and thus the bandwidth multiplier.

There’s a difference between time to receive and time to stop sending. Assuming each send attempt is independent, it takes on average 10 epochs for A’s message to arrive with B. Furthermore:

- A will send messages until it receives an ACK.

- B will send ACK if it receives a message.

To get an average of one ack through, A needs to send 100 messages, and B send on average 10 acks. That’s a multiplier of roughly a 100. That’s roughly what we saw with the simulation above for receiving a message in interactive mode.

Second case, high-availability caching layer

Let’s introduce a helper node or piece of infrastructure, C. Whenever A or B sends a message, it also sends it to C. Whenever A or B comes online, it queries for messages with C.

A message -> B (10% chance of arrival)

A message -> C (100% chance of arrival)

B <- req/res -> C (100% chance of arrival)

A <- ack B (10% chance of arrival)

C <- ack B (100% chance of arrival)

A <- req/res -> C (100% chance of arrival)

What’s the probability that A’s messages will arrive at B? Directly, it’s still 10%. But we can assume it’s 100% that C picks up the message. (Giving C a 90% chance success rate doesn’t materially change the numbers).

B will pick up A’s message from C after an average of 10 epochs. Then B will send ack to A, which will also be picked up by C 100% of the time. Once A comes online again, it’ll query C and receive B’s ack.

Assuming we use exponential backoff with a multiplier of 2, A will send a message directly to B at epoch 1, 2, 4, 8 (assuming it is online). At this point, epoch 10, B will be online in the average case. These direct sends will likely fail, but B will pick the message up from C and send one ack, both directly to A and to be picked up by C. Once A comes online, it’ll query C and receive the ack from B, which means it won’t do any more retransmits.

How many messages have been sent? Not counting interactions with C, A sends 4 (at most) and B 1. Depending on if the interaction with C is direct or indirect (i.e. multicast), the factor for interaction with C will be ~2. This means the total bandwidth multiplier is likely to be <10, which is a lot more acceptable.

Since the syncing semantics are end-to-end, this is without relying on the reliablity of C.

Caveat

Note that both of these are probabilistic argument. They are also based on heuristics. More formal analysis would be desirable, as well as better simulations to experimentally verify them. In fact, the calculations could very well be wrong!

Future work

There are many enhancements that can be made and are desirable. Let’s outline a few.

-

Data sync clients. Examples of actual usage of data sync, with more interesting domain semantics. This also includes usage of sequence numbers and DAGs to know what content is missing and ought to be synced.

-

Remote log. As alluded to above, this is necessary. It needs a more clear specification and solid proof of concepts.

-

More efficient ways of syncing with large number of nodes. When the number of nodes goes up, the algorithmic complexity doesn’t look great. This also touches on things such as ambient content discovery.

-

More robust simulations and real-world deployments. Exisiting simulation is ad hoc, and there are many improvements that can be made to gain more confidence and identify issues. Additionally, better formal analysis.

-

Example usage over multiple transports. Including things like sneakernet and meshnets. The described protocol is designed to work over unstructured, structured and private p2p networks. In some cases it can leverage differences in topology, such as multicast, or direct connections.